You Bought It; Don’t Break It!

October 5, 2019

Why Directors Should Create Disruption

December 30, 2019How Succession Anxiety Fuels Crisis

The transition from one chief executive officer to another is a high-stakes situation. In the most difficult situations, the outgoing CEO leaves a trail of damaged relationships, financial statements that are suspect, and a sense of relief that they are, at last, finally gone.

Usually, the difficult CEO has not prepared an internal successor, despite the board making this a mandate. Consciously or not, an insecure CEO doesn’t want the competition of a talented underling and their inability to manage themselves in this regard leads them to avoid the issue. That is, until the board brings it up. This is a big warning sign to the board that things are amiss.

Recalcitrant CEOs don’t seem to understand that it isn’t just their legacy they are playing with. A contentious succession process is destructive. It tarnishes the company. In the extreme, the issue leads to a crisis. The problem is that most boards and CEOs don’t realize when their situation has become extreme. The board of GE has, quite rightly, been criticized for leaving Jeff Immelt in the role far too long. The loss of value under his leadership is stunning. While hammering him is popular, he dealt with events outside of his control (9/11 and the financial crisis) that did great damage to GE. Nonetheless, his reported inability to listen to bad news (avoid anxiety) was of no help. His successor wasn’t given much time to right the ship. In this case, was the board more anxious in light of their own past complacency?

Why is it so hard?

First, the mere mention of succession ignites an array of thoughts, feelings and fears. Tension can develop between a board and a CEO and this is never a secret. The tension between Michael Eisner and the Disney board, Carly Fiorina and the board of Hewlett-Packard, Bob Nardelli and The Home Depot board are public examples. It doesn’t take an activist investor to prompt a crisis such as this, but that way often has a shorter fuse.

Second, if no good process exists to deal with succession, it isn’t so clear what to do. While it is just as negligent as not having financial audits, it is common for companies to be light on a process, never mind a plan. The problem is, the event will happen ready or not and if you don’t see it coming you can easily end up in a crisis.

Third, past success makes people blind. Fortunately, many companies successfully go through changes at the CEO level with either absent or weak succession processes. It’s messy, it takes a lot of explaining and calming of nerves. Usually, more talented people who wanted the job will leave. Yet, having come through a crisis, people breathe a sigh of relief, clean up any mess and go back to business as usual. Why pay attention to something that causes such angst? Furthermore, it feels wrong to talk to a newly appointed CEO about succession.

The Missing Link

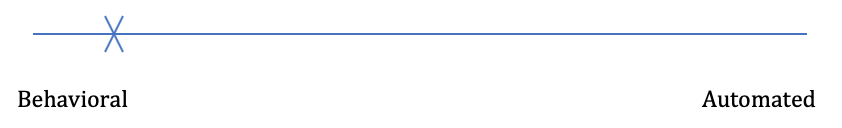

Top leader succession is a behavioral process. It relies on what people do. A fancy automated process can replace the attention and judgment of leaders. The continuum below shows where CEO succession falls between an automated process and one that relies on human action.

The reason the X is slightly to the right of the far end is because there is some information that can and should feed into a process such as leadership succession, without additional effort. These are the objective measures such as revenue, margin, sales, rate of growth, market share, etc. These are numbers that are, or should be, known for a given senior executive.

The other elements of succession require the attention of leaders. Its aspects are behavioral, attitudinal or based on capacity. Anxiety about the process often makes leaders seek out techniques and methods to reassure them. These are often invalid means and expose the company to needless risk.

There is no substitute for a disciplined process that utilizes the experience and judgment of leaders and no amount of anxiety justifies ignoring this critical responsibility. It’s high-stakes.